InstaPrayer: Share Your Meal

Photo Courtesy of @delphoss via Instagram

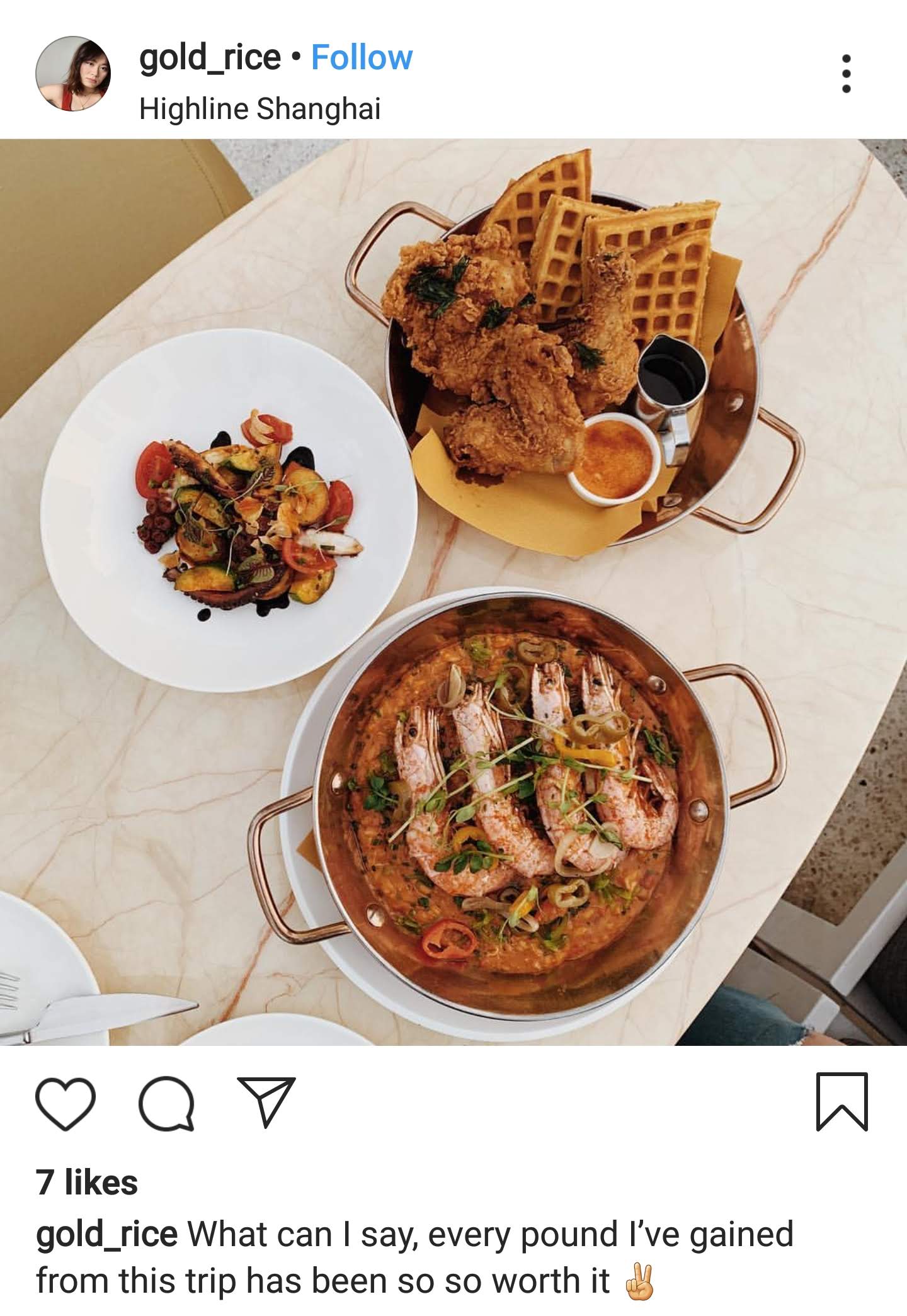

Everyone has experienced it, first hand or second: the food arrives and then you, or someone else, stops the table from eating to immediately photograph the food. “Nobody touch it!” the photographer exclaims as they take countless shots, changing the angle and position of their body, and shifting the plates and glasses to frame the photo to their specifications. The table waits patiently until the signal to eat, and social media has its 10 millionth post of food.

“#foodgasm #foodporn #food #forkyeah #noms #nomnomnom #foodpics #foodography #foodstagrammer #eater #goodeats #healthyeats #foodlover #foody #foodprayer #digitalprayer #foodpics #foodphotos #pictureofmeal #foodshots #iprayer #foodpraylove”

This occurrence is so familiar now, amongst some people, it has the suggestion of a ritual. The following will present a discussion of the (religious) act of praying before a meal and the pious offering of food to a “supernatural being.” Through content analysis of Instagram images, I surveyed photographs of food posts based on hashtags, occasions, and food type. The aesthetic investigation of the photographs in addition to the physical action will contextualize the ritual of the digital age. To be clear, this analysis will focus on images of food shared on public Instagram Feeds, not Stories, since your Feed is a more permanent, more public, space, while your Story is most often a temporary visual experience.

Our new daily routine is digital, social, and sometimes anonymous. The variety of social networking sites available to share, learn, and experience in a “disconnected” state is immeasurable. I chose Instagram for its well-known accessibility, so even though there are far more spaces available to create sub-genres for food-prayer analysis, “Instaprayer” became the act. The history of photographing food prior to a meal could begin with the introduction of the camera into everyday life, as the very way we view images daily is unlike anything the visual perspective has previously attempted. There exists a long history of the camera, camera obscura, and digital camera, however, the technological advancement of the camera (or cell phone) is not the focus of this discussion; the social, dialectic act of sharing photographs and the visual analysis of the images are. To what extent, if any, is the creation of Instaprayer indebted to previous visuals, rooted in the past?

We can define prayer as a discursive act that bridges human limitation and the spiritual realm; symbols and objects related to prayer have been uncovered as silent testimonials of ancient traditions and communities with a profound preoccupation with life and death in the construction and explanation of the social world (Lopez 197). Throughout history, religion has used the visual imagery, iconography, and ritual practices as tools to reinforce one’s faith in their religious ideology. Religious visual culture and rituals made their way into people’s everyday lives, in order to become a habit or even a necessity. Your seasonal or daily routine would include the prescribed tradition passed down from the religious hierarchy through the community or family hierarchy and these shared religious practices strengthened this communal and familial connection.

I grew up in a Christian family that prays before every meal; we called it grace. When we say grace, we bow our heads and bestow gratitude on our supernatural being for blessing us with nourishment and good health. There are, of course, variations for holidays or special occasions, but the daily prayer was simple, reciting, “Thank you Lord for the food we are about to receive and the nourishment of our bodies, in Christ’s name, Amen.” Although the term grace most commonly refers to the Christian tradition, numerous other religious groups pray before or after a meal - thanking God for creating everything. The act of grace can be private or public; no matter what, though, it is a part of a collective tradition, be it culturally, geographically or communally. Privately, grace teaches you not only to be grateful to the supernatural being of worship, but to value growth, life, sustenance, health, etc. Publicly, prayer before a meal allows one to share this religious tradition and its values with your community. Its habitual, repetitive nature reinforces these attributes, thus becoming part of your behavior and identity.

I opened the discussion describing an all too familiar scene - the individual(s) stopping to privately (in awe of the presentation) then publicly (posting to social media) give thanks for food. The difference in our digital age is that the gratitude is not offered to a religious icon but the uncanny social media site, and what it brings the photographer (worshiper): attention, likes, community, identity. This constant need to hear the bell ring, a priest notifying you of your miracle, shows a shift in social tradition and priority. For the majority of the social media community, the routine revolves around constantly monitoring your account and others’. An Instaprayer’s routine narrowly focuses on their food posts, constantly comparing themselves to that of professional food photographers, food bloggers, and food stylists. That social hierarchy passes down the aesthetic and content guidelines for the masses to follow. The attributes assigned vary from healthy to indulgent, as posts often increase when added to a personal diet, holiday, cooking goal, travel, or simply beautiful plate of food.

Votives and offerings are the physical elements of an act of personal piety presented to a supernatural being, performed in order to be seen. They inspire piety among wider populace and stand as individual or group testaments of the intensity of devotion (Gutierrez-Zarur 32). Retablos, painted panels, votives, ex-votos, and visual offerings are just a few examples that represent the intimate relationship to religion, creation of art, struggle to create life, and inevitability of death. While some strictly follow the church’s official predertmined iconography with very little stylistic innovation or experimentation, others are personally crafted and expressive of a specific narrative (Gutierrez-Zarur 32).

Late 19th Century Mexican Ex-Voto. ARTSTOR Collection: Fowler Museum (University of California, Los Angeles)

The approachable visual comparison of the Instaprayer’s presentation is to the ex-voto; derived from Latin, its meaning can be simplified to “the promise of,” “from a vow,” or “the miracle of” (Zarur 19). The structure of an Instaprayer, like the ex-voto, consists of three major elements.

The lower part contains the handwritten text with the description, at times highly detailed, of the event, with the date and place it occurred, the name of the affected person, and that of the person making the offering (if not the same) (Barta 27-28). The post’s description (i.e. inscriptions of ex-votos) sheds light on the relationship between the image and the giver, the commitment reflected in the hashtags (i.e. attributes).

The center of an ex-voto features the image of the story with bold primary colors used to express the spiritual and emotional content of the miracle portrayed. The Instaprayer often focuses on saturated contrasting colors or vivid patterns to visually pop from the screen composed symmetrically, the images feature a central point from which several axes can extend. The background often the table with several objects associated with eating a meal, flatware, napkins, and even beverages.

Lastly, the upper part, the “sacred site”, features the image or icon of a powerful mediator that seems to float weightless, celestial (Luque-Zarur 72). The aesthetic division here is between the spiritual realm of the supernatural mediator, Instagram, and the visible acts of the physical universe, prepared food. The image of the food is from a vow or for the promise of attention, likes, possibly even identity.

The aerial shot is the most important visual element - the view from above - that rarely includes any part of the human figure. Thus, this version of the Instaprayer scarcely features disturbed food; the story must show a complete dish, untouched and free from human interference.

Technically speaking, Instaprayer maintains the relationship to social media imagery through their structure and subject matter. There is little to no development in individuality as Instaprayers follow the prescribed iconography, style, organization and, of course, ritual action.

Instaprayer ultimately does have you interact with what’s on your plate. Each decision related to its aesthetics, camera angles, lighting, composition, and the placement of the additional objects (napkins, glasses, flatware) takes time and puts off any actual eating that might otherwise be happening, building anticipation for what’s to come.

I then stumbled upon a viral trend, a man who decides to interrupt this prayer, this preparation of a visual votive, and records the devastated reaction of the devotee. This disruption destroys the Instaprayer’s hopes of sharing their food; now that the predetermined iconography and visual standards are broken, the promise can no longer be fulfilled.

The last examples introduce the rare occasions when human hands appear in an Instaprayer. The overall structure remains the same with the lower, center, and upper spaces except here, the visual story presents or raises up the food towards the viewer, the devotee, and the “sacred site.” The gesture reaffirms the presentation of the food or vow and adds the element of communal sharing the food with you.

The stories of these Instaprayers place the devotee within the visual act, a hand holding the food and a bite taken, giving movement to the composition. We also see that the backgrounds vary from a table to scenic vistas, from an intimate space to a public one. The vivid colors, simplified forms and concentration on shape and contour define the recognizable signifier (the food) and the signified (hunger, desire, attention, likes, identity).

Wikipedia refers to the phenomenon as “camera eats first,” Urban Dictionary defines it as “digital prayer,” Social Media Today awkwardly named it, “Foodstagramming,” but the Internet is just as obsessed as I over this 21st century behavior, photographing your food before consumption and sharing it on social media. Instaprayer inspires a new form of piety among the social media populace and stands as individual or group testaments of the intensity of their devotion. The visual representation and physical act of Instaprayer has made its way into people’s everyday lives, becoming a ritual.

References

Art and Faith in Mexico: The Nineteenth-Century Retablo Tradition Ed. Elizabeth Netto Calil Zarur & Charles Muir Lovell. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque 2001.

Barta, Eli. Women in Mexican Folk Art: of promises, betrayals, monsters and celebrities. UK: University of Wales Press, 2001.

Baquedano-López, Patricia. "Prayer." Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 9, no. 1/2 (1999): 197-200. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43102465.

Gutiérrez, Ramón A. “Sacred Retablos: Objects That Conjoin Time and Space.” Art and Faith in Mexico: The Nineteenth-century Retablo Tradition.

Luque, Elin. “Powerful Images: Mexican Ex-Votos.” Art and Faith in Mexico: The Nineteenth-Century Retablo Tradition. 71-72.